There are

difficulties with developing an Interactive Narrative. Decisions should be made about the correct

balance of interaction and narrative, to keep viewers entertained and engaged

in the story. It is important to

remember that the telling of the story is the most important aspect in this type

of program.

From Winky Dink and You The Chocolate

Cookie Caper.

Cousin

Dorabell has made cookies for Winky and Woofer, but Harem Scarem has stolen

them. During the program interactions from the viewers will create a

spaceship and a vacuum cleaner to help foil his plot. The story ends with

Harem Scarem promising not to steal any more cookies, and Woofer eating the

fresh batch that Dorabell has just made.

Although the

story has a relatively simple plot, it uses strong characterisation and a

strong storyline as a basis to add interactions to.

An interactive narrative must allow room for the story to develop.

Care should be taken to avoid constant interactions, as this will distract the

viewer from plot, and may give the impression that the program is too similar

to a computer game.

From Winky Dink and You, The Vacation Draw-InTwo pirates sail in from the left.Big pirate: Okay matey- according to the map the treasure is buried right here.Big pirate points, and little pirate starts digging.Big Pirate: Well shiver me timbers- here it is, easy now matey.Small pirate lifts up treasure chest and hands over.Big Pirate: eeeh.Small Pirate: Hey- whatll we do with him.Small pirate points at Woofer.Big Pirate: He comes along, there aint no-one gonna be left to tell no tales.Small Pirate lifts Woofer into the boat.They all sail off to the left.

This scene

is used to introduce new characters to the story. It would be distracting

to include an interaction here, as the viewer is taking in the information

about the plot.

From Colin & Trouble in Space (NODAL NARRATIVE)Dr. Despicable sunbathing in front of the castle, with the sun looking through the bars.Sun: Why are you being so mean, I can't work properly when I'm locked up like this. The people on earth will be in the dark!Dr. Despicable: But I'm a villain, if I don't do bad things my reputation will be ruined.Sun: Please let me go, you can still see me if I'm in the sky where I should be.Dr. Despicable: No! I'm having fun.

Therefore: don't feel as though every scene must contain an

interaction. Some scenes can be used simply to build characters or to

move the plot forward.

http://i-media.soc.napier.ac.uk/patterns/storybuildingscene.htm

Balance

passive sections of the program with interactive sections giving the viewer a

chance to enjoy both the story and the participation. Use

characterisation and story to build a relationship with the viewer that will

make the interactions seem more relevant and crucial to the plot. Allow

on screen characters to talk directly to the viewer at home. This can

reinforce the feeling that the viewer is truly involved in the program.

When watching an interactive television broadcast it is important to

receive advance warning of an imminent interaction. The viewer knows

there will be an opportunity to interact at some point but does not know

when. This advance warning must be given in a way that does not interrupt

the flow of the broadcast.

In the Winky Dink and You episode

"U-boat in the Moat" the following dialogue alerts users to an

imminent interaction.

Winky: Don't worry King Kooky; the boys and girls in the audience will help us to get into the castle.Winky Dink takes control of the situation.

The next part of the story is established, this

helps make the viewer aware of the problem they will have to help Winky Dink

solve. He warns the audience that he will need their help, allowing them to be

ready with their crayons.

Colin: We'll have to get the kids to help us build a space ship.Trouble: Come on then I think I know where we can get some things to make it.Colin: Ah, the garage, good idea Trouble.

In EverGrace

(2001), The

Bouncer (2000) and Enter The Matrix

(2003) the viewer is prepared for an imminent interaction by the changes in the

interface which are specific to the type of interaction to come:

For example

in EverGrace

(2001) an image such as a red dagger appears over an enemy to prepare the

viewer for an attack. This warns the viewer of when and how they are expected

to interact.

Therefore: use the natural flow of the narrative to signal when a viewer

will be expected to react.

There is

potential for many different kinds of interaction even within one

broadcast. Interactive tasks undertaken to enjoy the full effect of a

program may not necessarily be familiar, and may require instructions.

The giving of the instructions should not detract from the story.

Television programs are designed to entertain, so instructions must be given in

a way that will make the purpose of the task clear without appearing too

formal.

The computer

games The

Bouncer (2000), Enter

The Matrix (2003) and EverGrace

(2001) all use a combination of formal and informal instructions to inform the

viewer of what is required. Informal instructions are contained in the dialogue

of the storybuilding scenes:

For example,

in Enter The

Matrix (2003) informal instructions as to the purpose of the character's

task are delivered by another character Sparks whose duty it is to relay

information while formal instructions as to how to complete the task are

contained in the interface:

Therefore:

Use the

relationship between the user and the characters, by allowing characters to

explain what is required. Reinforce spoken instructions with visual

instructions. In this way instructions can seem to become part of the

narrative and disruption to the flow of the program is minimised.

An informal

explanation of the task can also be explained from one character to another.

Accompanying formal instructions can be displayed discretely but clearly at the

bottom of the screen. By not having to directly address the viewer and break

their immersion in the story there will be minimal disruption to the flow of the

narrative.

Therefore:

always praise a viewer when a task has been completed successfully. The

praise can come in the form of a character thanking the viewer for their help,

or can be shown in more subtle ways. If an action of the viewer has

allowed the story to move on, this can be considered a form of praise- the

viewer gets to see the results of their actions.

Therefore:

allow the story to move on even when a viewer has been unsuccessful in

completing a task. Take the opportunity to be positive about the

situation. This may involve a light-hearted joke or a comment from a

character, or an alternative visual sequence where the task that has been

failed is shown to be solved allowing the narrative to move forward.

Therefore:

create main storybuilding scenes that drive the plot and contain all the events

and information crucial to a basic understanding of the story. Create

additional storybuilding scenes which are specific to the parallel stream

chosen and which provide parallel information and perspectives on events that

enhance the viewer's understanding of the main story.

http://i-media.soc.napier.ac.uk/patterns/awarenessofcrucialevents.htm

Character based

interactive parallel narrative

Character

based interactive parallel narrative allows the viewer to switch between

characters at certain junctures in the narrative. The aim of character based

interactive parallel narrative is to give the viewer a unique and more in-depth

comprehension of the story by allowing the viewer to follow events from not one

but many different character perspectives.

Character

based parallel narratives currently exist in both interactive and

non-interactive media:

In literature such as

Dickens's Little

Dorrit (1857) - the book is split into two parallel narrative strands, one

showing events from a rich person's, Clenman's, perspective and one showing the

same events from a poor person's, Little Dorrit's, perspective. The

juxtaposition of these contrasting character perspectives of the same events is

used by Dickens' to highlight the inequalities in the society of the time

between the rich and the poor.

Authors use

character based parallel narratives to juxtapose different character

perspectives and show:

- the underlying themes of the story.

- the discrepancies between different characters' perspectives of an event by showing it in parallel with a contrasting perspective of the same event from a different character.

In character based

interactive parallel narratives, however, the author has less control over the

juxtaposition of these perspectives because the viewer can choose which

character they will follow and therefore which perspectives they will

juxtapose. Understanding the affect this 'free' juxtaposition of character

perspectives will have on the viewer is key to creating a meaningful and

enjoyable interactive experience.

Location based interactive parallel narrative

Location based parallel narrative allows the viewer to follow events that occur in a particular location. The aim of location based interactive parallel narrative is to give the viewer a unique perspective on the story, characters and events, according to the location they have chosen to watch events.As with character based parallel narrative, location based parallel narratives exist in both interactive and non-interactive media:

In theatre such as Norman Conquests (1973) by Alan Ayckbourn -the theatre production is staged on three consecutive nights. On each night the viewer watches the same events of a dinner party, but from a different location (either the living room, the kitchen or the garden) and as such their overall perception of events and characters changes each night according to the extra information gained from watching another of the three location based parallel narratives.

In location

based interactive parallel narratives the author has less control over which

location the viewer follows and therefore what information is hidden from the

viewer in order to affect their perspective of events.

Therefore: use parallel narrative when you

wish to allow the viewer to select a path or perspective through the storyline

without being able to change the course of events.

http://i-media.soc.napier.ac.uk/patterns/parallel.html

Interactive Media @ Edinburgh Napier University

http://playwithlearning.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/linear-traditional.png

http://playwithlearning.com/tag/narrative/

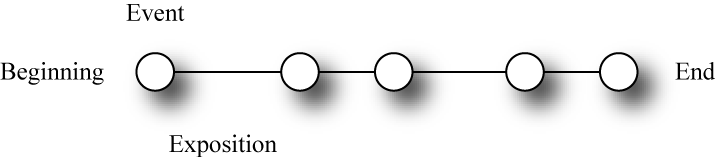

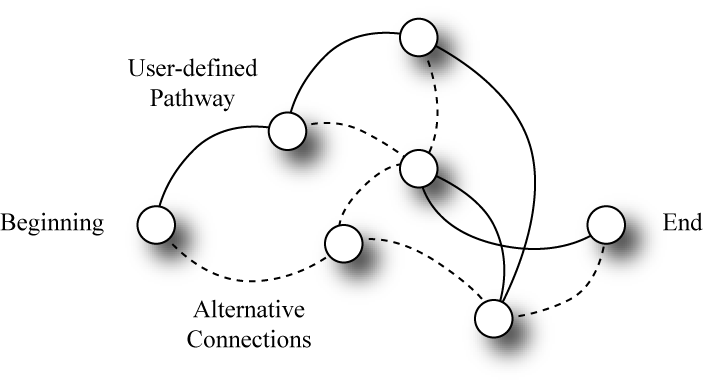

Parallel

paths offer the user two distinct paths and ‘junctions’ where the tracks

combine. This allows the user to experience consequences of his chosen

actions but returns him to predetermined points where the story can advance in

a more managed way. By hopping from node to node like this, the user has

a high sense of control even if his experience shares much with that of other

users. For example, BioShock allows

users to decide on one of two strategies: ‘Kill Little Sister’ or ‘Save Little

Sister.’ Each option has a unique set of challenges and consequences but the

paths come back together at key points in the game, allowing the user to

continue with their chosen course or switch approach.

http://playwithlearning.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/parallel-paths.png

Parallel

paths overcome some of the production challenges of a strict branching

narrative by reducing the total number of tracks down to just two.

This limits the options even further than the constrained branching narrative

model but still allowing a level of user choice.

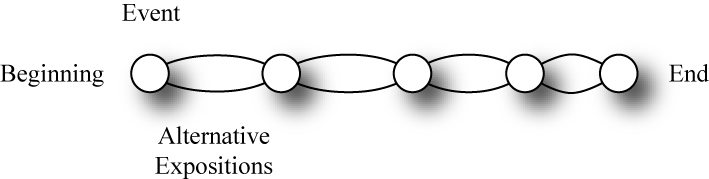

Branching

Narratives

Instead of a

single continuing storyline, branching narratives offer the user consequential

choices. Each decision offers a unique path in an ever-diversifying array

of events. Although the total outcomes will be finite, branching

narratives give the user control over the course of the action. Rather

like changing the points on a railway line, branching narratives allow the user

to determine the direction of the train, and therefore its destination, but not

the path between points. The game designer determines all the available

options but the user decides the route through them.

In a truly

branching narrative, every decision has a unique set of consequences.

This reflects real life where every choice provokes an avalanche of outcomes

where future options are a direct result of an individual’s behaviour.

There are circumstances in reality when an individual’s choice is illusory and

just as when this occurs in real life, the facade of control

in games is quickly obvious and deeply unsatisfying. The opportunity to

genuinely choose the path of discovery offers the user real control but every

true option generates at least two outcomes. The combinatorics quickly

become unmanageable from a production perspective. Even offering the

minimum of two choices per decision at each stage the number of outcomes

multiples exponentially, according to the simple equation o = 2s

where S is the number of stages. For example, it is clear that three

stages result in eight possible outcomes.

http://playwithlearning.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/branching.png

The

constraints of the production mean that narrative cannot be entirely

free. Instead, producers regularly draw the narrative back to shared

nodes. These nodes appear as the consequence of possibly unrelated

decisions and provide a means of limiting the range outcomes.

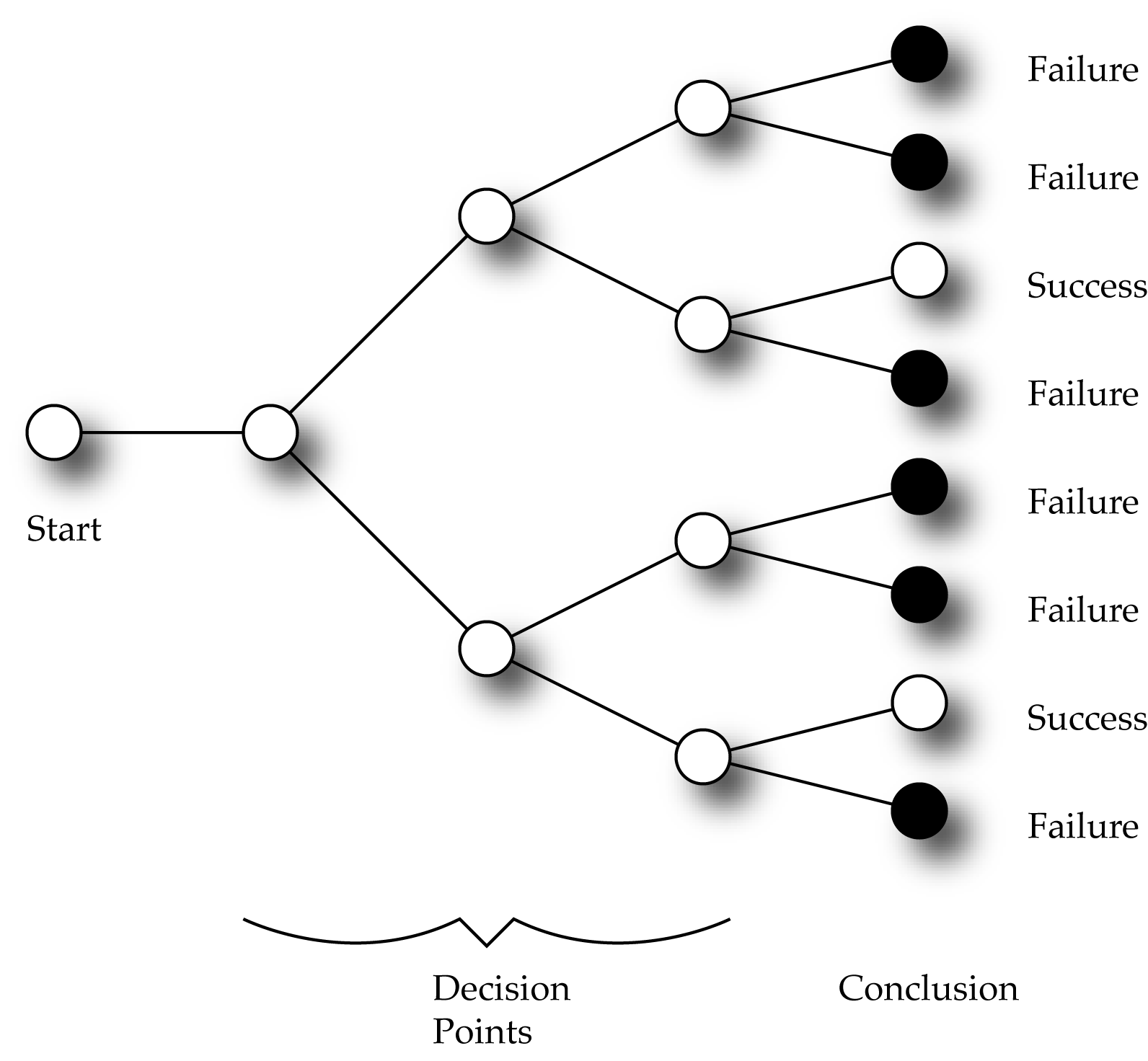

These dynamic experiences may contain discrete storylines (in the form of implicitly linked events) but have multiple connections to other event nodes built into them. This allows the user to construct a narrative at will and where the relationship between characters or the plot revelation unfolds unpredictably.

Visual Novels

http://www.visualnovelty.com/images/screenshots/screenshot3.jpg

http://www.visualnovelty.com

Novelty is a free game maker tailored for making visual novels. Contrary to most other visual novel makers, Novelty is designed for people without any experience in scripting or programming.

My Candy Love is a web-based visual novel. It conforms to the typical styles of visual novels however it has a weak script and the options for the events are very stiff - in the sense that they are all quite similar to each other so they do not allow a sense of freedom of choice.

http://minescope.wordpress.com/category/games/lux-pain/

Lux Pain is a better example of a Visual Novel. Although it has a few elements of game play (minigames in order to progress with the story) Lux Pain is still largely narrative based. It works interactivity into the the narrative in a number of ways. The first is through character interaction, then through the minigames and finally with location based interactivity (not parallel because going to a one location or another may change the outcome, however most of the time it's possible to go them them all). Lux Pain is largely a dynamic visual novel.